Missing Mom

Yesterday and today, I’ve been reading posts from the month of October eight years ago, when Mom died on Oct. 27, five days after my 50th birthday. I was surprised my blog posts from that time were not showing up in my Facebook memories. I’m guessing whatever sharing option that existed back then isn’t operational anymore – or something like that. I don’t even know how to articulate the technology. This blog was always low-tech, just a basic journal. If I had tried to make it more attractive visually, I may not have kept with it. I can follow instructions for posting on the web, but I have never been willing to figure out anything but the basics by myself for the purposes of blogging. I’m actually finding writing here now unfamiliar and different, so I just hope I don’t mess it up.

I’ve been thinking about writing about missing Mom for a while. And it relates to a podcast. I started listening about two months ago to Julia Louis-Dreyfus’ podcast Wiser Than Me, in which she interviews older women – actors, musicians, writers, activists – about aging and recollections of their younger years. I really enjoyed it, but was taken by surprise when I started choking up at the end of the first episode, when Julia called her mom to talk about the interview she had done with Jane Fonda. I love it that she worked her mother into the podcast. I envy the close relationship she has with her mom, whom she often calls Mommy. And I thought, every time I listened to her calls with her mom at the end of each episode, that I was robbed of the chance to talk about aging with Mom.

It’s been about 20 years since I first started wondering if something was wrong with Mom – I initially thought it was a hearing problem, but I also thought of her as skipping a beat sometimes, being unable to follow a conversation or confused about finances. I was 38, she was 66. Neither of us knew at that time that we were already running out of time to have meaningful conversations. I hope the disease process actually protected Mom from being aware of the loss of function as it happened, even when it seemed subtle. And I was young enough that I didn’t think of the life lessons I still wanted to learn from Mom. I had to age to realize how much of that I lost. I remember writing about “the long goodbye” concept of Alzheimer’s in 2014 and how misleading that phrase is – because there is no meaningful goodbye with this disease.

Now that I’m closing in on 60, there are lots of things about aging that I’d like to be able to discuss with Mom. She was an intellectual, and funny, and endured a lot of personal and professional struggle in her life. I suspect she would have had a lot of insight to share about navigating the sometimes unfriendly world as a middle-aged and older woman, and would have helped me understand that there are so many things that just aren’t worth worrying about. I worry about so many things that I can’t control, and I still worry about what people think of me – sometimes, at least, but not in all contexts. Bonnie struck me as someone confident in her decisions and actions, even if fallout followed. I can be willful and speak my mind, and when I do, it’s because I think it’s the right thing to do. But I often second-guess myself, too. I’d like to have a mom around to tell me I shouldn’t fear being true to myself.

Maybe writing this, and drawing on what I recall about her life, will help change my frame of mind. I’ll never stop missing her. But I can gain strength from my memories.

Breaking the ice

Mom died five years ago. Today, I burned, recycled and threw away some of her mail from the early 2000s. It was the first batch of her many belongings in my basement that I’ve gone through since she died.

I’m used to having a messy basement. I grew up in a house with a ridiculously messy basement. At the bottom of the steps, we took a sharp left turn to access the narrow path to the washer and dryer in the back room, where the furnace was. When I was finished with a toy or grew out of my clothes, I’d go to the bottom of the steps and toss whatever I was discarding into the pile of family junk that filled up most of the main room.

Our basement in this house has gone through phases in the 22 years we’ve lived here. The woman who owned the house before us let her dog use the concrete basement floor as a toilet, so it started out bleachy-clean. Over the years we’ve accumulated various household goods and, in 2007, we stored a bunch of Mom’s things downstairs after we moved her out of an apartment and in to assisted living. Were I more organized, I might have discarded mail dating back to 2001 at that time, but I didn’t. Nor did I organize the hundreds of loose photos that were scattered around her apartment. While she was still sick, I couldn’t bear the thought of doing any more work related to Mom than what I was doing as her caregiver. After she died, I pretty much shut down to completing any task related to Mom. And I’ve stayed that way for five years. So her belongings have remained untouched.

In January 2019, we renovated our kitchen, and moved most of our kitchen items to the basement. With some of those things still downstairs gathering dust and a pandemic elliptical machine in the process of being shipped, we have reached an agreement: We will spend some amount of time every day working on getting the basement in order. (For the record, Patrick is much more dedicated to this kind of work. I find it overwhelming – even though it in no way resembles the basement of my childhood.)

So today, after doing some organizing in the laundry area and setting aside clothes for donation, I grabbed an accordion file folder of Mom’s labeled “Mail to go through.” I sat on the living room floor with Mom’s file folder and sorted the contents in three piles: fireplace, recycling bin, trash.

Things that caught my eye:

- Mom looked into cremation in 1996 – nine years before she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

- Mom paid certain bills in installments, and wrote notes to herself about how much she had paid on what date, and how much she still owed.

- Mom had collections of different kinds of stickers – smiley faces, Christmas trees, dogs. I kept the dog stickers.

- Mom had a CT scan of her abdomen in 1997. I remember vaguely that she told me – after she knew she was OK – that she had had a health scare. That she had been concerned she might have pancreatic cancer. At the time I was hurt that she hadn’t told me earlier. But now I understand – and the parallel strikes me as … perhaps meaningful, but probably just a coincidence?

- I had a CT scan of my abdomen Monday. I got my results today – all clear, no abnormalities in any organs and an update on the misaligned vertebrae in my lower back that I’ve known about for years. I talked to my doctor about unexplained lower abdominal pain a few weeks ago, and she ordered the scan out of an abundance of caution. I saw on the order today that the screening was for possible gynecologic cancer – which I understood was probably the case, but hadn’t been explicitly stated. I haven’t told anyone about that scan except for two colleagues, but in only vague ways. There was nothing really to tell people because I didn’t know anything. Why cause alarm when I didn’t have any answers? I assume Mom felt the same way. That said, it did cross my mind several times this week that I wished Mom were around to talk to while I waited for my results.

When I’m 54

Though I don’t care much about the transition to a new year, I was perfectly happy to put the 2010s behind me — a decade marked by the death of both of my parents, and the hardest of my caregiving years with Mom. In 2020, I thought, I could focus on looking forward rather than getting hung up on past sad events.

And then I got sick, on Jan. 2. And I couldn’t talk to Dad about it. Even as a middle-aged adult, I want to talk to Dad when I don’t feel good. That’s just how it has always been. In my case, having a physician for a Dad has meant talking to him about all kinds of ailments, whether they’re related to his specialty or not.

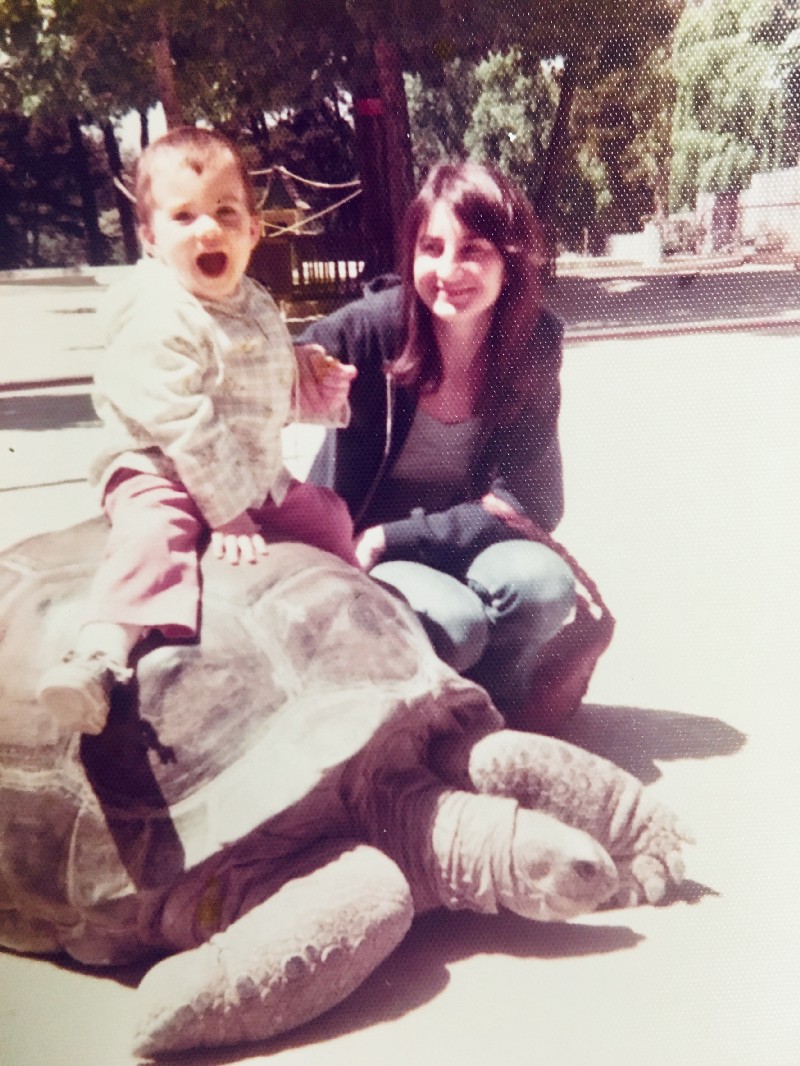

My sister Laura talking to Dad during our summer vacation in 2018. I believe they had some discussions about health, too.

What started as a cold morphed into an ear infection and then, after 10 days of antibiotics, I had an apparent recurrence of viral symptoms that still bother me somewhat to this day, more than four weeks since it all began. And I feel very sorry for myself. Missing Dad does not help.

I don’t know that I would have called Dad about this particular bout with bacteria. But I put something on Facebook about taking antibiotics; Dad, a daily Facebook user, would undoubtedly have checked in on my timeline to see how I was doing. And then probably would have again a few days later. (I am confident this would be the case because Dad makes frequent appearances in my Facebook memories, which is both wonderful and heartbreaking.) Being sick has also meant for most of my adult life that I should stay away from Dad because, because he was a transplant patient, his immune system was suppressed. He spent one whole winter several years back fighting what he suspected was whooping cough. So minimizing his exposure to germs was important.

This has evoked many childhood memories of my various illnesses and accidents. Poor Dad was called in for doctor duty even though we didn’t live with him after my parents divorced. When I was very young and fell on my face in a neighbor’s driveway, he took me to University Hospital at Ohio State to get stitches in my forehead. When the wound had healed, he came over to remove my stitches as I lay draped across his lap in a chair. I was squirmy and did not make it easy for him. He visited when I got chickenpox, and he identified the reason my throat was so sore, which was an abnormal symptom: I had a chickenpox blister on my uvula.

I had multiple cases of tonsillitis as a kid, and as a result my tonsils are enormous. I wanted to have them removed but Dad said no. “They’re there for a reason.”

In eighth grade, I had an astounding total-body case of poison ivy. To this day, I don’t know how I got it, but my body responded as if I had rolled in it. My face was in full crust mode by the time Dad came by to examine me. “You look like the Incredible Hulk,” he said. I cried, being an unrecognizable 13-year-old girl who itched from head to toe, and was therefore very sensitive. He took me to a dermatologist colleague’s house after work on that occasion, and we left with a prescription for a tapered dose of steroids that cleared me up quickly.

I have small veins like Dad did, so blood draws can be complicated. In high school, I helped organize a blood drive. Near its conclusion, I sat down to make my first blood donation. The Red Cross staff could not find a good vein — though not for lack of trying, by poking me in the arm repeatedly. I was embarrassed, sore and upset, and that failure was so memorable that I have never tried since to give blood. I got mono later that year. Dad took me to the hospital to confirm the diagnosis, and I told the phlebotomist she’d have a hard time drawing my blood. She rolled her eyes and got the sample she needed on the first try. I’ve always been thankful to Dad for taking me to her.

Most recently, in 2018, he talked to Patrick and me through our cases of influenza — my mild case, thanks to my annual flu shot, and Patrick’s lengthier case that involved taking Tamiflu. And Dad, a gastroenterologist, was the obvious go-to when Patrick had diverticulitis. They had a couple of marathon phone sessions talking about symptoms and treatment options.

As I blogged about Mom, I was often frustrated that I didn’t have very strong memories of my day-to-day life growing up, and that many of my memories related to negative events. Similarly, memories of my weekly visits, along with Jeff and Laura, with Dad after our parents divorced are not vivid. But the memories I do have about my encounters with him during my childhood are much more likely to be positive, even if they revolved around being sick. My guess is the value of having his attention increased dramatically after he no longer lived with us. In fact, I have no memories of our family life — or of any part of my life — before he moved out, save for a select few isolated events — like how my neighbor friends made fun of me for walking around shirtless when I was about 4, trying to be like a boy.

I should have known that the start of a new decade wouldn’t make one bit of difference in how I think about my life. The past is important — especially as I age and try to draw on lessons I’ve learned, or remind myself of problems I have solved, or take pride in what I’ve accomplished personally and professionally. And, most important of all, as I remember my parents, and others, who are gone, with the benefit of wisdom and gratitude that comes with the passage of time.

Resolution in memoriam

The most important vote taken today by Ohio State’s Board of Trustees, in my humble opinion, was approval of the resolution in memoriam honoring my dad. I’ve pasted the text in below – the pdf is hard to read.

Synopsis: The Board of Trustees of The Ohio State University expresses its sorrow regarding the death on June 5, 2019, of James H. Caldwell, MD, Professor Emeritus of Internal Medicine in the College of Medicine.

Professor James Caldwell did his undergraduate and medical school training at The Ohio State University, receiving his MD and acceptance into the Alpha Omega Alpha honor society in 1963. He completed his internship in Medicine at the University of Chicago Hospitals only to return to The Ohio State University College of Medicine to serve as a junior assistant resident in Medicine from 1964-65. His residency training was interrupted by a call to service in the United States Air Force, where he served as a Captain from 1965-67. Dr. Caldwell then completed his residency in Medicine at The Ohio State University Hospitals, as well as a fellowship in Gastroenterology. He joined the Ohio State faculty upon completion of his fellowship in 1970, and rose in the ranks to full professor in 1981.

His numerous accomplishments in medical research and education endeared him to his peers and trainees. During his tenure at Ohio State, Dr. Caldwell served as an investigator with the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs and was the associate director of the Independent Study Program from 1994 to 2001. He was nationally recognized as a leader in the study of intestinal digitalis glycoside transport, as well as eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and was awarded multiple extramural grants in relation to this field of study. He also received numerous honors and awards for his teaching contributions to the College of Medicine. Most notably, he received the Outstanding Teacher Award for the Problem-Based Learning Program in 1992, and participated in both national and local post-graduate courses.

Dr. Caldwell was on staff as a highly respected academician, researcher and clinician for 38 years. He was an outstanding role model for medical students, trainees and his peers, and he brought a humanistic approach to medicine. He received a heart transplant in 1994 and continued to work until his retirement in 2008. During his recovery from his heart transplant, he found solace in gardening. Through the help of OSU Extension, he became a Master Gardner and continued his training in life.

He was a truly wonderful person, physician and scholar, and he was first and foremost dedicated to his family. He is survived by his wife of 46 years, Dr. Patricia Caldwell, a physician in her own right who was also his colleague. She retired from Ohio State’s Division of Cardiology in 2009, and continues to hold an appointment as Professor Emeritus.

On behalf of the university community, the Board of Trustees expresses to the family of Professor James Caldwell its deepest sympathy and sense of understanding of their loss. It is directed that this resolution be inscribed upon the minutes of the Board of Trustees and that a copy be tendered to his family as an expression of the board’s heartfelt sympathy.

Poetry

At Dad’s memorial service, my sister Laura read a poem she had written in February 1994. By this time, Dad had been hospitalized for several months, waiting for a donor heart. And my niece Julia, Laura’s daughter, selected a poem to read for the service. I have been meaning to share them here for some time.

THE WAITING

by Laura Caldwell

Everywhere I look I see your heart.

It’s pulsating on the stove in the meat sauce

marinating with sugar and cumin to fill

my children’s plates and stomachs.

And woven into a wool muffler it

circles my daughter before it shapes

my lips as they kiss the rose on her cheeks.

Imprinted in the gauze of a band-aid

stuck to my skin, it continues to

dress subtle abrasions and inflamed wounds.

So solidly are your arteries built

into the bricks of my mantel, I cannot imagine

that blinking embers could still.

If only I could collect all of these

hearts, graft them into a valentine and

deliver them to your sterilized room,

Maybe then your new heart would come.

Written February 14, 1994. Dad received his heart 10 days later, on Feb. 24, 1994.

TRAIN RIDE

by Ruth Stone

All things come to an end;

small calves in Arkansas,

the bend of the muddy river.

Do all things come to an end?

No, they go on forever.

They go on forever, the swamp,

the vine-choked cypress, the oaks

rattling last year’s leaves,

the thump of the rails, the kite,

the still white stilted heron.

All things come to an end.

The red clay bank, the spread hawk,

the bodies riding this train,

the stalled truck, pale sunlight, the talk;

the talk goes on forever,

the wide dry field of geese,

a man stopped near his porch

to watch. Release, release;

between cold death and a fever,

send what you will, I will listen.

All things come to an end.

No, they go on forever.

from In the Next Galaxy © Copper Canyon Press, 2002

Eulogy: Two hearts

At long last, I am publishing the eulogy Patrick wrote for Dad’s memorial service, which was held on Monday, June 10, 2019.

On display during calling hours and the celebration of Dad’s life: Pat made the quilt as a gift for Dad’s 75th birthday. The family photo was taken during a Caldwell family vacation at Bald Head Island several summers ago. The piece at right was a gift to Dad upon his retirement from Ohio State’s medical center. The cane lying across the front of the stand was made for Dad by a grateful patient.

We Caldwells didn’t trust ourselves to get through a eulogy, so Patrick was recruited. He labored over it for hours and hours with just a few days to prepare. After the service, a friend asked me if I had written it, because I am a writer. But no, this comes straight from Patrick’s heart and mind and affection for Dad. And we thought it was perfect.

Two Hearts

I’m here to try to tell a story. This is my story.

We are here to remember and honor James Hudson Caldwell, MD. He was born March 27, 1939, in Bellaire, Ohio. His parents were Robert M. and Goldie Caldwell. He has a brother, Bob.

He graduated from Shadyside High School and earned his undergrad and medical degree at THE Ohio State University. He skipped grades between elementary and high school and he completed his undergraduate degree in 3 years. He was a gastroenterologist at The Ohio State University Medical Center.

In Columbus, Ohio, on Dec. 22, 1956, Colo the gorilla became the world’s first gorilla born in a zoo setting…

That’s quite a transition.

In the early 1970s, Colo was having GI issues. A call for help and James Caldwell came to the rescue — imagine a shirt with a colon shaped into an S.

Colo was the first gorilla born in captivity and Dr. James Caldwell was the first physician to perform a GI procedure on a gorilla — in Columbus, Ohio, U.S., North America, the world, etc.

Emily remembers that the procedure occurred in the grass: Colo, Dad, and a zookeeper. As the anesthesia began to wear off, Colo gave a little squeeze of Dad’s arm. OK, I THINK IT IS TIME TO END THIS PROCEDURE.

Although he was accomplished academically and professionally, this man saved the life of a gorilla!

He shared with me that one of his greatest regrets was not making the Ohio State University Marching Band as an undergrad. His gait made it difficult for him to march, so he didn’t make the cut.

I’m somewhat surprised that this incident did not lead him to study orthopedics for a few years, just for the fun of it.

He served in the U.S. Air Force in Grand Forks, North Dakota. He was a longtime model train enthusiast.

I also grew up in a small town that had a rail line running through it. So I grew up, possibly like Dad: Windows open in the summer. I would hear, late at night, the sound of the train, coming from somewhere, but also moving on.

That sound, for me, will always take me to that time. The sounds of trains are evocative for me.

Jim was, however, the practical environmentalist: trains and light rail can be an efficient and carbon-neutral form of mass transportation. But he also dreamt of the Caldwell Memorial Monorail that would connect campus and downtown.

I think trains also took him back…

He was a loving husband, father, grandfather, and father-in-law.

For those of you who did not know me in the 1980s or 1990s, I used to have hair…a lot of hair. In 1988, when I first met Dad — Karl Marx, Albert Einstein, Bozo the Clown. I wanted to be Marx. I knew I would never be Einstein. But I think Jim — Dad — probably thought BOZO. And looking back, I can’t disagree.

After college, Emily and I spent some time apart. Emily went to Maine to work as a journalist. She covered George Bush Sr. in Kennebunkport, Maine. (I think her work on the “recycle-gate” controversy led to Bush Sr. being only a one-term president. Ask her about it.)

I went to Kentucky for grad school to study sociology. The sociology department once gave me an award for having the hair that was most similar to Bart Simpson’s hair. I was still struggling.

Then in early 1994, two hearts began the process of bringing Emily and me back together. They were not our hearts. Jim had a heart transplant. My dad, a quadruple bypass and valve replacement.

We reconnected over our fathers’ hearts.

Later in 1994, Emily and I got engaged. I’m certain that I spent time with Dad and Pat before our wedding in 1995, but it was at our wedding that I knew Jim loved me.

While Dad was a conversationalist, in 1995, he could be a bit circumspect when it came to verbally expressing emotion. So he expressed his emotions through his actions.

I was crying a bit during our wedding, and couldn’t get to a tissue or handkerchief. I think this touched Jim.

We were married in a barn, on a little stand in the middle. Families facing each other…the Hatfields and Corleones.

When I came off of the stand, he caught me and held me. I will always remember that hug and the love I felt in that moment.

From then on, I was lucky enough to have a second father in Jim.

I had a dad in Ohio in addition to my dad who ended up living in that state up north (O-H…) [Yes, attendees responded with I-O.]

I think Dad appreciates that response.

My mom still roots for the Bucks.

Dad was a Master Gardener.

Dad enjoyed a good meal.

Fish Fest became a Christmas Eve tradition.

At the end of the Fish Fest, at the end of any meal or any visit, we would say it was time to leave, and never go. Dad would start another story or continue with the story he was telling.

We always had more to say, more stories to share. We just wanted to spend a few extra moments together. Even when it was time to go, we wanted to hear one more story.

Dad was born in a small Ohio town.

He loved trains.

He helped save the life of a gorilla and the lives of actual people.

He loved gardening and the environment.

He was always on the lookout for a new restaurant and a good meal.

He gave a great hug.

He was a loving husband, father, grandfather, friend.

He will always be with us when we tell our stories of him.

Dad’s heart

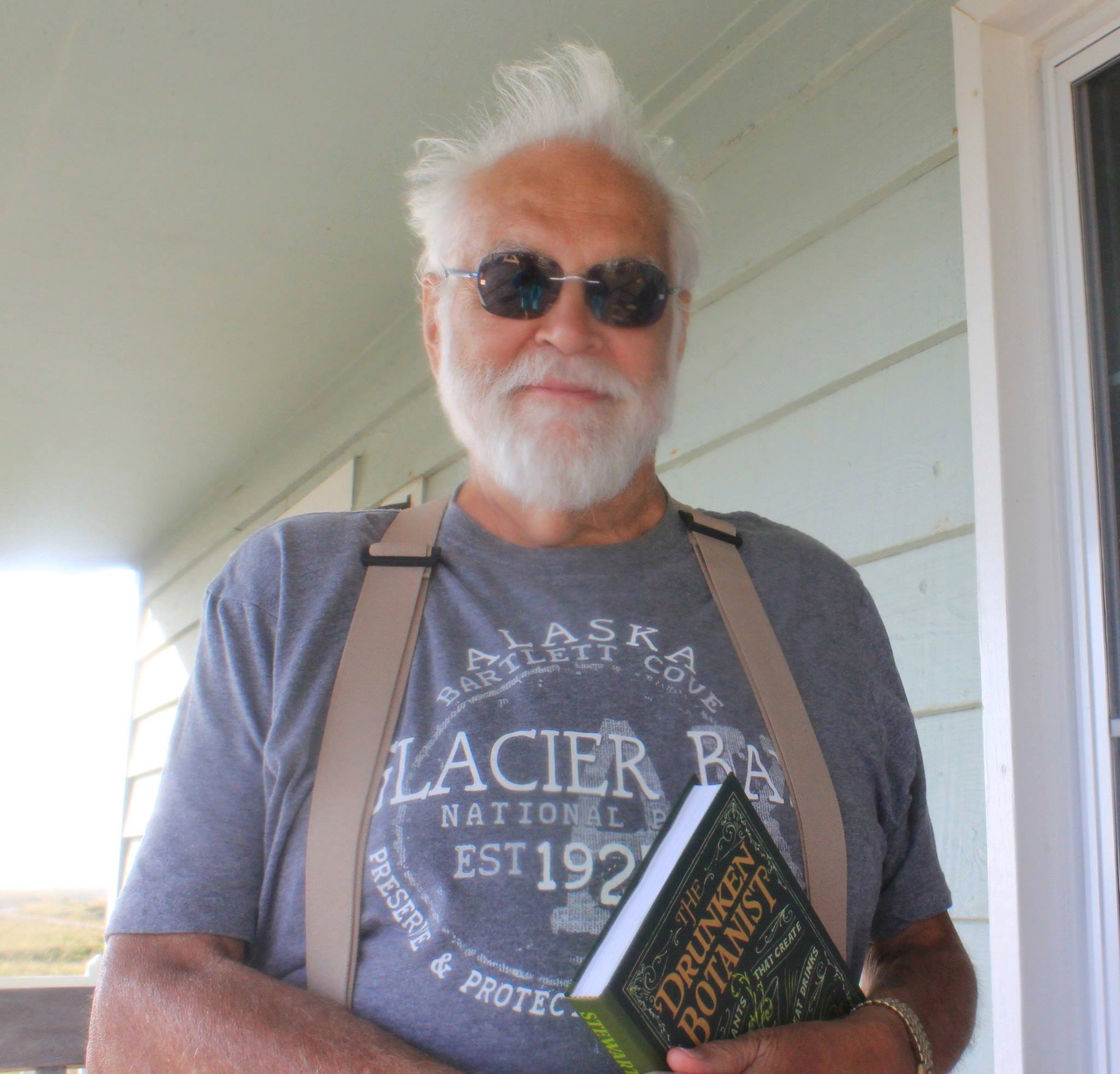

A girl can get greedy, and become disillusioned, when her dad has a heart transplant in 1994 and is still around to celebrate his heart day every Feb. 24 for 25 years. And then celebrates his 80th birthday. I considered 2019 a good year for my dad, James H. Caldwell, MD. His birthday was on a Wednesday in March, so we planned to whoop it up in his honor in July at Bald Head Island, our beloved Caldwell family vacation spot. We will still observe that birthday and celebrate his remarkable life in late July. His seat will be empty, but he will be with us.

A girl can get greedy, and become disillusioned, when her dad has a heart transplant in 1994 and is still around to celebrate his heart day every Feb. 24 for 25 years. And then celebrates his 80th birthday. I considered 2019 a good year for my dad, James H. Caldwell, MD. His birthday was on a Wednesday in March, so we planned to whoop it up in his honor in July at Bald Head Island, our beloved Caldwell family vacation spot. We will still observe that birthday and celebrate his remarkable life in late July. His seat will be empty, but he will be with us.

Dad died at around 9 p.m. Wednesday, June 5, at Ohio State’s Ross Heart Hospital. He had been hospitalized for 10 days for what began as a GI bleed. Multiple tests failed to identify the source of the bleed, and it eventually stopped after he was taken off his blood thinner. He experienced a slowed heart rate during one test, leading to some electrophysiology testing and procedures. His last procedure, to check for clots in his atrium (no clots found), was successfully completed Wednesday afternoon. He’d be in for observation for two days and home by the weekend. And then, disaster struck, in what we assume was a pulmonary embolism, or perhaps a massive heart attack.

Being in the hospital meant Dad was missing valuable late spring outdoor time. A lover of gardening for as long as I’ve been alive, he became a Master Gardener through OSU Extension over the many months of his recovery after his heart transplant. The house he and his wife Pat have lived in since 1991 has an enormous yard with room for vast perennial beds and a sizable vegetable garden — one of its major selling points. Poor Dad could never convince me to love gardening. I like the cosmetic and culinary results but I hate the work. But he had tomatoes and peppers that were ready for planting, pronto, and I was tasked with getting that done. I took it seriously, following his instructions and the layout he had drawn on a scrap piece of paper. “Lord help me if they don’t thrive,” I joked in a text to my siblings.

I enjoyed sending text updates over the past week to my brothers and sisters, who live in Seattle, Iowa, Grand Rapids, Cleveland and Brooklyn. The news about his health was always pretty good. Dad lost his temper one day with the medical staff because he was frustrated with the poor communication among the various teams working on his care – two different heart services and the GI service. His spirited response conveyed he had energy, an improvement over his weakness from anemia when he entered the hospital. And yet, for a long time he was what I describe as fragile, physically. Immunosuppression drugs take a toll on the human body, and he had osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, stress fractures, muscle detachments, renal failure and I don’t even know what else. He had a bad infection last summer that set him back further, but, as a very compliant physical therapy patient, he rebounded nicely.

With Mom, whose death I anticipated for 10 years, I found myself surprised about how devastatingly sad I was when she died, considering I wanted her suffering to end. Dad has been fragile for many years, but was always fine with minimizing acknowledgment of his physical limits. So all of our conversations at the hospital over the past 10 days were characterized by an expectation that he would go home, take some time to regain strength, get back to the garden and ride in the car with me and Patrick for the trip to Bald Head Island. And so, his death was unexpected. And of course, I am devastatingly sad, while I am also so grateful that he lived as long as he did.

Dad was a master diagnostician, an educator, an intellectual, a conversationalist and storyteller, a lover of classical music, a foodie, an avid consumer of news and information, and, since the early 2000s, a progressive political activist. He and Pat were devoted to each other, and spent very little time apart over the course of their long marriage. And he leaves a legacy in his kids who, along with our families, are smart, talented — musicians, writers, poets, scholars (we all have postsecondary educations) — thoughtful, temperamental, driven by conviction, funny and a little bit (or a lot) cynical, and, like Dad, have a healthy appetite for delicious food and all of the joys, big and small, that life has to offer.

Guest post

Caregiving blogs are, themselves, terminal in nature. So far, I have not opted often to write here instead about grief or some other kind of remembrance. My friend Misti Crane did not know Bonnie, but she knows mourning the loss of a mother and she knows writing. She published the below post on Medium, and I asked if I could include it as a Momsbrain guest post. I’m so glad she said yes.

On perfume and permanence

How Mom is still with me after 7 years

Sibs in the City

And just like that, three years have passed since Mom died. Oct. 27 was the anniversary of her death.

Earlier this month, Laura, Jeff and I spent a weekend together in New York to celebrate Mom. The year she died, we got together shortly after her funeral for a November weekend in New York, where Jeff and Laura lived at the time. We decided then that we would gather each fall for a weekend in memory of Mom. I call it Sibs in the City. And we have kept that promise to ourselves.

Below is a photo of us having drinks at the Whitby Hotel in New York on Oct. 6 after seeing a matinee of a terrific play. Our annual agenda would be roughly the same if Mom were along for the trip: some moderately fine dining, but nothing too fancy; a Broadway show – or two, or three; a little shopping; a museum exhibit if we can fit it in; blocks and blocks of walking; and time for a midday nap.

It is something positive associated with losing our mom.

We texted each other on Saturday (Oct. 27), Jeff first.

Jeff: Happy Mom day. Thinking of you two.

Me: Same to you. Will be writing a blog post. Love you.

Laura: Love to you both. You and Mom have been on my mind today.

Mourning the loss of a parent is an unpredictable experience, and we all grieve in our own way. I’m grateful, though, that the three of us have elected to lean into the shared experience, so at least sometimes, we don’t have to do it alone.

Suppression impossible

Why was I breathlessly anxious while walking my dogs this morning?

Why did a bag of spoiled cauliflower in the fridge make me so mad?

Why can’t I recall a single bit of the funny podcast I streamed in the car on the way to work?

Why do I feel that mild sting of potential tears in my eyes?

Hello, heartburn.

Oh, yes. I guess I’m trying to trick myself into forgetting. Today is Mom’s birthday. She would be 81.

Happy birthday, dear Bonnie.

Mom blowing out candles on her birthday cupcakes in June 2009 at a little party Patrick and I threw for her at the Park of Roses. This was just two months before she transitioned from assisted living to the Alzheimer Care Center. She looks so good.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment